The fallopian tube is an amazing and versatile reproductive organ. Its functions include capturing an egg from the ovary at the time of ovulation; nourishing the fertilized egg or zygote during its early cell divisions; and delivering the blastocyst into the uterine cavity when it is time for implantation. The different parts of the fallopian tube correspond to these various functions.

Tubal Anatomy

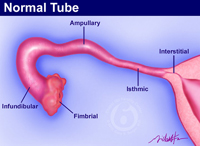

The end of the tube furthest from the uterus is the fimbria. The fimbrial segment is lush with cilia that beat vigorously and sweep the egg into the tube where it is fertilized. The egg is quickly moved by the bell-shaped infundibular segment into the ampullary region of the tube. Over the next several days, the combination of muscular contractions and ciliary movement move the egg toward the uterus. The ampulla provides nourishing fluid that allows repeated cell divisions. When the dividing egg (zygote) reaches the stage where the outer membrane dissolves (blastocyst), it is time to be delivered into the uterine cavity. This is the function of the muscular isthmic segment of tube closest to the uterus.

The end of the tube furthest from the uterus is the fimbria. The fimbrial segment is lush with cilia that beat vigorously and sweep the egg into the tube where it is fertilized. The egg is quickly moved by the bell-shaped infundibular segment into the ampullary region of the tube. Over the next several days, the combination of muscular contractions and ciliary movement move the egg toward the uterus. The ampulla provides nourishing fluid that allows repeated cell divisions. When the dividing egg (zygote) reaches the stage where the outer membrane dissolves (blastocyst), it is time to be delivered into the uterine cavity. This is the function of the muscular isthmic segment of tube closest to the uterus.

Does Anatomy Predict Function After Tubal Reversal?

Given the complexity of the functions of the fallopian tube, one might wonder if any portion is essential for pregnancy to occur. Years ago, based on the information available in medical texts, I assumed that there would be essential parts or a minimum length of tube needed to result in a normal pregnancy. However, there was little information available to answer this question. Therefore, I began recording the portions of tube removed, tubal segment lengths remaining, and other details about each patient’s reversal operation in an electronic database. Since the staff members at A Personal Choice follow-up with patients regarding pregnancy after tubal reversal, it has become possible to study the interaction of tubal anatomy and the tube’s ability to function normally.

A Surprising Discovery

Over the 30 years that I have been performing tubal reversal procedures, I have seen every variation of tubal ligation imaginable regarding the sections of tubes removed and lengths of tube remaining to repair. It was surprising to learn that no specific part of the fallopian tube is absolutely required for pregnancy to occur. Somehow, the fallopian is able to compensate for the loss of specific parts and still function normally! Based on this knowledge, I am optimistic in being able to repair any kind of tubal sterilization procedure with the expectation that it will allow the possibility of having more children.